The Week Before

A taste of "Moses and the Doctor"

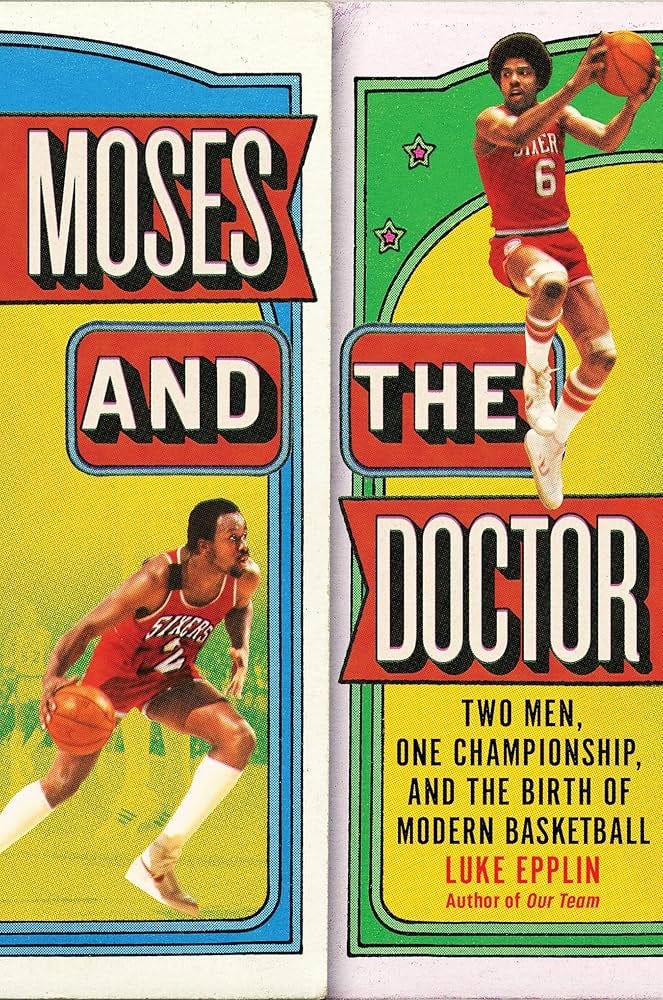

I’m one week away from the publication of Moses and the Doctor. It’s exciting but frightening: exciting because I’m proud of the book and look forward to getting it out into the world, and frightening because I want the book to find its audience, which is never a given. To induce folks on the fence to give the book a chance, today’s newsletter will include a snippet of the Introduction. If you like what you see here, then please consider giving the rest of the book a shot. See you on publication day.

On October 30, 1974, the New York Nets flew to Salt Lake City to face the Utah Stars. It was the Nets’ fifth game in six nights, all in different cities. The punishing schedule spoke to the grind of playing in the American Basketball Association, the monthslong blur of predawn wake-ups, airport layovers, and half-full arenas. But that evening promised to be different. Even though the Stars had staged their home opener for the 1974–75 season a week earlier, the franchise had held off on any festivities. The Stars were taking a big risk that year, and the front office recognized that their unprecedented experiment required a blessing from the undeniable face of the league—the MVP, the scoring leader, the defending champion. They were waiting for Dr. J to arrive.

From the moment he’d surfaced on the national stage as a sinewy, scarcely known forward, his Afro flared high and the ABA’s distinctive red-white-and-blue ball swallowed up by his enormous hands, Julius Erving appeared a vision of the future, an avatar of a sport that was shifting from the ground to the air. Like compatible puzzle pieces, the ABA and Erving had locked into place at once. One was a fledgling start-up scrambling to disrupt the National Basketball Association’s hold on the sport’s top talent, the other a leaper from Long Island who’d amassed a cult following on the asphalt courts of New York City. Erving carried that playground sensibility into the ABA, complete with an alter ego, Dr. J, whose balletic moves defied belief.

But few saw them. Because no television network broadcast ABA games nationally, Dr. J remained more rumor than reality, a ghost in the machinery of professional basketball. “I heard the legend of Dr. J, and I said, ‘That’s bullshit.’ Until I saw him in that game,” remembered Calvin Murphy, a five-foot-nine dynamo for the Houston Rockets who first competed against Erving in a charity contest during the early 1970s. “When I saw him sit on the rim, take them big hands, and dunk that ball over my whole team, I said, ‘Yep, it’s for real.’”

Despite possessing the sport’s most electrifying player, the ABA struggled to stay solvent. In a league characterized as much by instability as by flamboyance, Erving at times seemed the difference between treading water and sinking. To chip away at the NBA’s supremacy, ABA executives threw whatever they could think of against the wall, gimmicks and three-point shots and slam-dunk contests. The Utah Stars went so far as to nab a hoops prodigy straight out of high school.

In the third round of the 1974 draft, the Stars selected a nineteen-year-old center who’d sailed to two state championships at Petersburg High School. For months, college recruiters had camped out in south-central Virginia, promising Moses Malone the world if only he’d sign his name to their commitment letter. While Malone had eventually settled on the University of Maryland, his true desire had been to bypass college altogether. And that was exactly what he ended up doing.

It was a risky, controversial gambit. Detractors charged the Stars with robbing an adolescent of his education; sportswriters questioned whether Malone’s gangly frame could withstand the pounding from men many years his senior. To calm skeptics’ nerves, cautious Stars officials turned to the ABA’s most beloved and distinguished asset.

The night before Halloween in Salt Lake City, a crowd some seven thousand strong hustled to their seats. Like many arenas of the era, the Salt Palace, a cream-colored structure shaped like a snare drum, had minimal pregame entertainment—no loud music, no scoreboard antics, no dance troupes. What they had instead was Erving, clad in the patriotic colors of his Nets warmups, staging a one-man dunking exhibition in the layup line. For audiences not yet weaned on nightly highlight clips, the spectacle would’ve been as thrilling as the game itself. But then Erving did something unexpected. He strolled to halfcourt and grabbed hold of the public-address microphone.

Even though he was only a half decade older than Malone, Erving, in his fourth season out of the University of Massachusetts Amherst, had already assumed the responsibilities of an elder statesman. A master improviser on the court, he’d learned to deliver what was expected of him off it as well, no matter how peculiar or unconventional, such as praising a competitor in another team’s arena. The impromptu speech Erving gave before tipoff was equal parts stirring and comforting, befitting someone whose postgame interviews poured out of him with such fluency that they came across as scripted.

“My high school coach once told me that when you go into the ocean for the first time, you cannot expect to swim right away. First you have to get your feet wet.” Erving then turned to Malone. “But, Moses, you have been thrown into the ocean, and you can swim already.”

The person least moved by the speech was its subject. The press conferences, the magazine profiles, the highway billboards that heralded his arrival in Salt Lake City, the pregame praise from a renowned competitor—none of that interested Moses Malone. Basketball was his passion; the public-facing obligations that those who played the sport at the highest level had to fulfill were, for Malone, irritants to be swatted away. He would no more give a follow-up speech thanking Erving than he would strip naked at halfcourt. Wringing words out of the lone teenager in professional basketball already was taxing the most seasoned sportswriters. Malone’s approach to his job was as blunt as his demeanor: suit up, sweat and bang, go home.

The philosophical gap between the two individuals off the court manifested in different ways on it. That evening, Malone controlled the paint; Erving managed the flow. Every time a shot went up, Malone broke hard toward the basket, sidestepping defenders, worming through gaps, tipping misses to himself. New York head coach Kevin Loughery watched in disbelief as the Stars rookie grabbed fifteen rebounds, nearly half of what the entire Nets roster pulled down. “You don’t expect an eighteen-year-old or whatever he is to come out and play like that,” Loughery marveled.

Held to two free throws in the first quarter, Erving exploded for thirty-four points over the next three. Malone kept pace with twenty-eight of his own. At one point, Malone caught a pass inside the foul line, spun around his defender, and, according to Steve Rudman of the Salt Lake Tribune, “nearly ripped the basket from its moorings in one of the grandest stuffs ever witnessed, reminiscent, in fact, of the thing that made Erving famous.” Erving countered with what Rudman characterized as “aerobatic rushes, vacuum dunks and the neatest rendition of rhapsody in a blur there is in basketball.” It was a battle between two equal but opposing forces: smooth and rough, graceful and grinding, ice and fire. In the end, a three-pointer—an ABA invention that the NBA wouldn’t implement until 1979—by Erving sealed the game for the Nets.

After his team’s 95–91 win, a reporter asked Erving for an assessment of the adolescent whom he’d publicly praised beforehand. “In two words,” Erving responded, “I believe.”

Over the following eight years, Erving and Malone switched leagues and clubs, won MVPs and shattered records, honed novel styles of play and endured postseason heartbreak. Along the way, the speech bound them together. Whenever they faced each other, Malone would sidle up to Erving and ask, “How’s my swimming going?”

Every basketball fan is familiar with the rivalry in the 1980s between Earvin “Magic” Johnson’s Los Angeles Lakers and Larry Bird’s Boston Celtics. It was, according to legend, the matchup that helped the NBA shed its reputation as a drug-addled, violence-prone league and blossom into a sporting juggernaut whose appeal spanned continents. But this binary between Magic and Bird, the Lakers and the Celtics, has overshadowed other players and teams from this pivotal era that were every bit as instrumental in shaping basketball as a sport, an art form, and a cultural phenomenon. None more so than the two ABA expats who eventually banded together on the Philadelphia 76ers to disrupt the decade-long title swaps between the Lakers and the Celtics.

This is the story of the rambling road that led Moses Malone and Julius Erving to each other. Opposite in temperament and antithetical in approach—one having reimagined the way that basketball was played on the ground, the other in the air—Moses and the Doctor meshed seamlessly, their strengths and weaknesses in perfect counterbalance, establishing a blueprint for future superteam pairings. Together, they set out to accomplish what no other club fronted by stars from the ABA had managed. More than a championship, it was legitimacy they were chasing, not only for Erving’s playground-infused style and Malone’s unorthodox path but also for a defunct league whose freewheeling, expressive spirit has since come to define basketball across the globe.

Great story, strong framing, lively writing. Augurs well, good luck!

🔥🔥🔥