The Staging of One of Baseball’s Most Famous Images

The Steve Gromek/Larry Doby Photo Revisited

On October 9, 1948, the Cleveland Indians, up two games to one in a tightly contested World Series against the Boston Braves, turned to a spare part in their pitching rotation. Even though it’d been three weeks since Steve Gromek had last started, in Game Four he matched Braves ace Johnny Sain pitch for pitch. It wouldn’t have been enough if another unlikely player hadn’t bailed him out. Larry Doby, the first Black player in the American League, someone who hadn’t even been slated to crack the Indians’ roster coming out of spring training, roped a Sain curveball over the chain-link fence in right field, granting Gromek a two-run cushion in the third inning—just enough for him to cruise to a 2–1 victory.

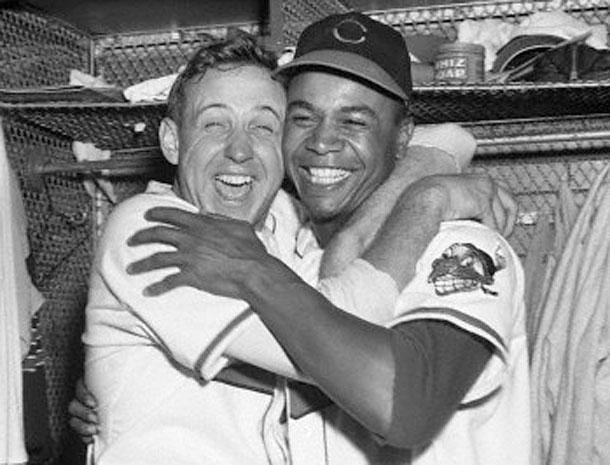

In the Indians clubhouse afterward, Gromek, the son of Polish immigrants from Hamtramck, Michigan, sought out Doby, the descendant of enslaved ancestors from Camden, South Carolina. Newspaper photographers snapped an image of the two locked in a cheek-to-cheek embrace, their eyes nearly shut in ecstasy. The following morning the picture ran on front pages across a country still beset with segregation, the first image that many Americans would’ve seen of white and Black colleagues celebrating a shared accomplishment together.

Those are the bare bones of how a photo that retains its power and meaning more than three quarters of a century later came into being. But what if it’s more complicated than that? What if that image had been staged? Would that dilute its significance?

For me, the photo of Gromek and Doby was an endpoint. All narrative roads led there.

When I started working on the proposal for the book that became Our Team, I’d never written a chapter before, never published anything longer than seven thousand words. For weeks after I signed the book contract, I was seized with stomach cramps every morning around ten. For fifteen minutes I’d squat on a toilet lid at work, waiting for the panic to pass. During that first year, I tried mapping out the narrative across hundreds of notecards and on pages of yellow legal pads. I wrote fifty thousand words and still hadn’t made it past chapter four. I neglected to drink water and passed a kidney stone. I muttered to myself so loudly on the sidewalk in Queens that fellow pedestrians jaywalked to avoid me. I was lost.

The photo kept me anchored. I knew that if I somehow could drag the narrative in that direction, I’d have a book. I could visualize the words on the page, the readymade climax I was muddling toward—Gromek bounding into the locker room, out of his mind with emotion, and spotting the teammate whose homerun had ensured that the game hadn’t extended to extra innings. I imagined the hug as spontaneous and unself-conscious, a release of emotions that Larry Doby had kept bottled inside ever since he’d crashed the majors cold out of the Negro Leagues fifteen months earlier.

I had no beginning, I had a murky middle, but oh boy did I have an ending.

At least I thought so.

When I finally made it to the World Series chapters after two years of false starts and dead ends, I paused to conduct some last-minute research from newspapers that I’d yet to scour. In the archives of the Boston Herald, I dredged up an article entitled “Indians Wait for ‘Big One’ to Celebrate.” It had been published on October 10, 1948. Neither a game summary nor an opinion piece, the article instead was a sort of ethnography of the Indians locker room in the moments after their Game Four victory.

Its author, Will Cloney, who later would gain renown as the longtime race director of the Boston Marathon, wandered about the clubhouse, interviewing players, observing the scene, and gauging the mood of a franchise on the cusp of its first World Series championship in twenty-eight years. Most members of the Indians were subdued, unwilling to celebrate until they’d clinched the title—with one exception. Aware that his postseason service was likely complete, Gromek whooped and hollered with what Cloney described as the giddy energy of “an excited schoolboy.” The press gathered around him, sensing that here was where their snippets and images for the next morning’s editions would come.

It’s worth quoting Cloney in full, since what he documents is the most vivid and detailed description that I came across of how the photo between Gromek and Doby happened:

“Steve [Gromek] had a 20-minute course in dramatics, with two dozen photographers yelling conflicting directions at him. Co-starring was laughing Larry Doby, whose third-inning tee shot to right-center produced the winning run. They talked calmly until all the photographers were ready. Then, at a signal, they hugged each other like a couple of performing bears. Those were the ‘spontaneous’ shots the still and movie photographers recorded for posterity.”

My heart sank while I read this paragraph. I’d drafted Our Team not as an historical monograph but as a propulsive narrative whose climax (I’d assumed) would be the photo. But how powerful could this climax be if it’d been staged?

I studied the photo for so long that I risked reading too much into it. It started to reveal itself to me as a reflection of where Gromek and Doby stood at that moment, as much in their careers as on the Indians. Years earlier, during the final two years of World War II, when the military draft had drained professional baseball of many of its best players, the undrafted Gromek had won twenty-nine total games for the Indians. In the three seasons since, he’d logged a mere seventeen wins. His 1947 season had been so undistinguished that Gromek was the only member of the Indians’ roster whose salary team owner Bill Veeck had slashed. Even though he wasn’t expected to pitch in the 1948 World Series, player manager Lou Boudreau named Gromek as the surprise starter of Game Four partly so that Bob Feller could avoid a rematch with Johnny Sain, who’d outdueled the Indians ace in the opening contest. As a not-so-subtle jab at Gromek, Boudreau spoke of the team’s willingness to “sacrifice” the game. The emotions that Gromek released after he went on to pitch the game of his life seemed to come as much from relief as elation. Staring straight at the cameras, his left arm bent around Doby’s neck as if he were about to wrestle him to the floor, Gromek laughed like a man who’d just bought himself another half dozen seasons in the majors.

Doby, in contrast, draped his left arm across Gromek’s chest, taken aback seemingly by the ferocity of Gromek’s feelings and his willingness to express them so openly in public. Since he’d shown up on the Indians straight out of the Negro Leagues on July 5, 1947, Doby had had to cope with segregated accommodations, racial abuse, and teammates who’d staged what sportswriter A. S. “Doc” Young called “an iceberg act, allowing him more space on the bench than any player in the history of the game.” It’s no wonder that in the split second after Gromek grabbed him, Doby appeared somewhat uncertain about whether he should pull his teammate close or push him way. Doby looked, in short, like someone who’d spent two summers starved of physical intimacy of any kind from his teammates. “The picture,” Doby told his biographer, Joseph Thomas Moore, decades later, “finally showed a moment of a man showing his feelings for me.”

Just because the photo had prompted by the press didn’t make it any less real for the two men who would be forever linked by the image. It was no less real for Gromek, who returned home and got the cold shoulder from his childhood buddies at a Hamtramck bar because they disapproved of his unabashed celebration with a Black teammate. It was no less real for Doby, who later asserted that the photo meant more to him than the homerun that had given the Indians the margin of victory. And it was no less real to journalists of the era, especially those at African American newspapers, including Marjorie McKenzie of The Pittsburgh Courier, who wrote that that picture was “capable of washing away, with equal skill, long pent-up hatred in the hearts of men and the beginnings of confusion in the minds of small boys.”

I had my climax after all. What I came to realize is that how the photo came into being didn’t matter nearly as much as the impact it had—and continues to have seventy-seven years later. Not wanting to “print the legend,” I shied away in Our Team from describing the encounter between Gromek and Doby as unprompted. But neither did I dwell on the beat-by-beat steps that brought the two together on that fateful afternoon. It was enough for me to know that when given the opportunity to express the emotions they were feeling, both in their own way did so honestly and unhesitatingly.

Thank you. Fantastic.

Beautiful.