Of Batons and Brawls

Calvin Murphy's extracurricular pursuits

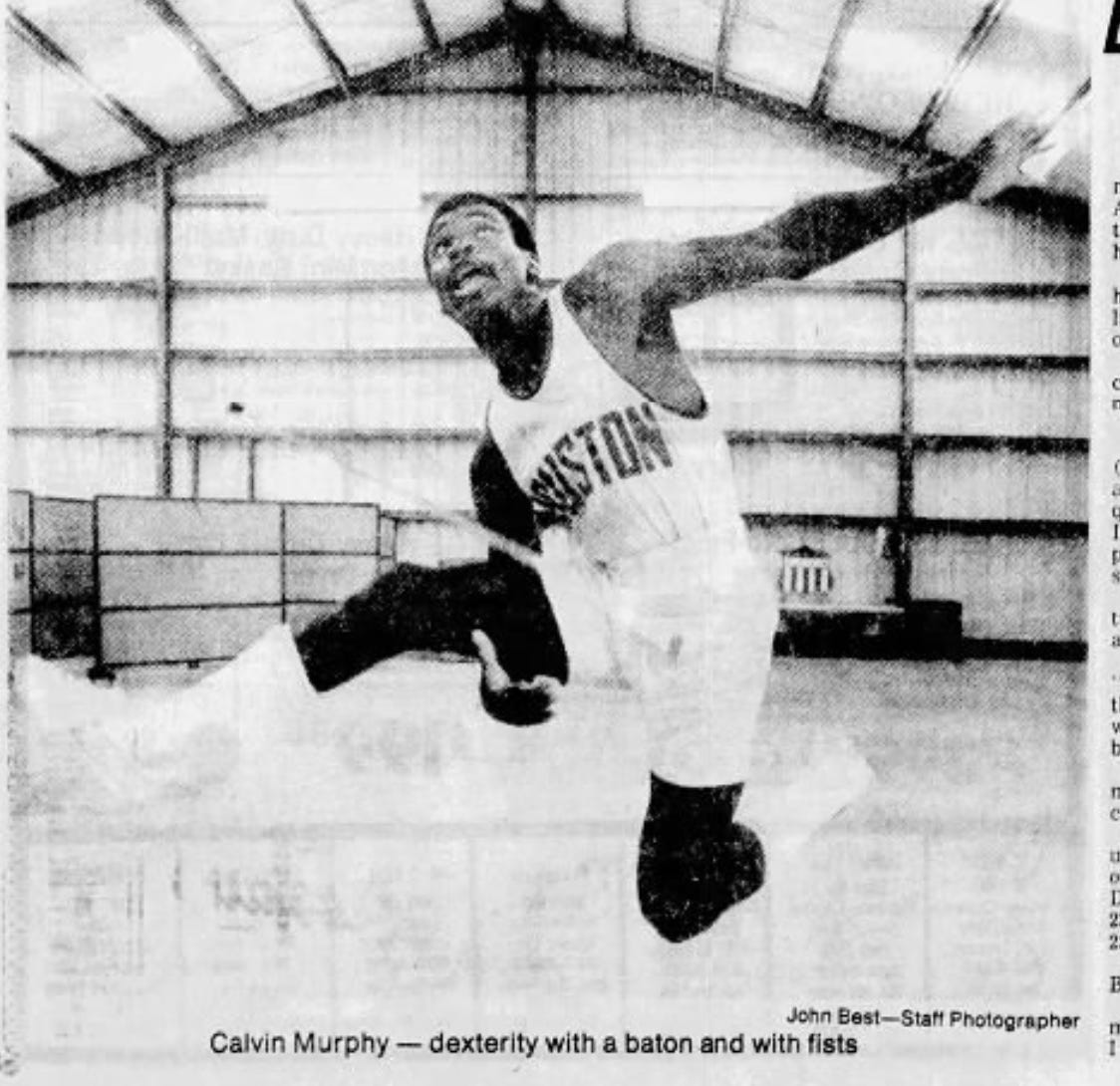

It’s four weeks until Moses and the Doctor comes out. Here’s a short post on a minor figure in the book, Calvin Murphy, whom I interviewed about his time playing with Moses Malone. I didn’t know during the time of our interview that Murphy once had been a nationally acclaimed baton-twirler.

An hour or so after the Houston Rockets had upset the Boston Celtics in Game Two of the 1981 NBA Finals, Calvin Murphy, the Rockets point guard, hailed a taxi from his hotel in downtown Boston. Three strangers approached him, claiming to have flagged down the cab first. “These guys called me a bunch of racial names,” Murphy told me last year by phone. “I thought they were going to jump me. So of course I struck first and one of them went down. The others backed off. They had nothing to do with me after that.” As Rockets trainer Dick Vandervoort said about the incident, “They didn’t know who they were dealing with at all.”

At five-foot-nine, 165 pounds, nothing about Calvin Murphy, in street clothes or in uniform, suggested that he was a basketball player, let alone one of the NBA’s foremost enforcers. Murphy had, according to forward Sidney Wicks, a “small man’s complex.” Not only did Murphy, a Golden Gloves boxer in his youth, level Wicks (6-foot-8, 235 pounds) with several rapid-fire punches during a game in 1976, but he did the same to Dale Schleuter (6-foot-10, 235 pounds), Larry McNeill (6-foot-9, 235), and John Brown (6-foot-8, 230 pounds). The scuffle with Brown left the power forward with six stitches, a split lip, and a bloody nose. “I’ve never faced anything like that whirlwind,” Brown said afterward. “[Murphy was] so quick, he got in five or six good punches before I could hit him. I want to issue a warning to other NBA forwards and centers: Stay away from Murphy.”

This reputation as a giant slayer enabled Murphy to weather any teasing that might’ve blown his way because of his favorite off-court activity: baton-twirling. Growing up in Norwalk, Connecticut, Murphy was given twirling lessons by several of his aunts. He took to the baton so enthusiastically that he practiced with it more than two hours each day. In high school, Murphy split his time as a point guard on the basketball court and a baton-twirler in the band. By age fifteen, he’d become the Connecticut champion in baton-twirling and the runner-up in the 1963 World Baton Twirling Championship in New York City.

Unsurprisingly, twirling batons elicited unkind comments from classmates. “There was some teasing when I was in junior high,” Murphy remembered, “but I wasn’t bothered much because they knew I would punch them out.” Once, while Murphy was performing at halftime during a football game, an out-of-town student asked who the “sissy” in the white uniform was. Word traveled back to Murphy. “He played basketball for another school,” Murphy recalled, “and the next time I saw him, I scored forty-five points against him.”

For four years at Niagara University, Murphy averaged an astounding thirty-three points per game while traveling occasionally on Sundays to twirl during halftime shows at Buffalo Bills’ games. His introduction to the NBA, a league then dominated by hulking centers, was rocky at times. Once, before a game against the Bulls, a security guard refused to let Murphy enter Chicago Stadium. “I had to raise hell,” Murphy remembered. “I kept telling him, ‘I’m with the Houston Rockets.’ I took my uniform out of the bag and showed it to him. He still wouldn’t let me in. Finally, they had to go and get the trainer to let me in the place.” But as he’d done in college, Murphy defied the odds. “Several years ago,” Murphy said midway through his thirteen-year career on the Houston Rockets, “I was too small for this league, but there are a lot of 6-9 guys selling insurance who came in with me.”

As always, Murphy continued to twirl batons (here’s a video of him in action), and certain teammates continued to snicker. “The other guys do things like marching by my locker with brooms for batons,” he said with a laugh. But there was genuine affection and admiration, too. Once, during a fundraising dinner that Murphy held in Houton for the baton-twirling troupe that he sponsored, Moses Malone, a three-time NBA MVP and a gruff presence on and off the court, slipped into the room, handed Murphy a bag stuffed with thousands of dollars, and then disappeared before Murphy could announce his presence.

Ultimately, baton-twirling was integral to Murphy’s athletic journey, which ended with his induction into the Basketball Hall of Fame. “Exerting your will on that baton, making it do exactly what you want it to requires tremendous concentration and self-discipline,” Murphy said. It was the same discipline he needed to survive as an undersized guard in the NBA, and the same domination that was required to put bigger men in their place. “Every time I see Calvin Murphy, I want to sneeze on him,” shooting guard Terry Furlow once said. “But I know better.”