Boxing the Unboxing

Or Why I'll Never Be a Social Media Standout

My wife traveled to San Francisco last week for a conference. The day she left, my editor informed me that the final copies of Moses and the Doctor were imminent. Instead of feeling excited, I panicked. Who would film my unboxing video now?

It’s a question that wouldn’t have crossed a writer’s mind when I broke into book publishing a quarter century ago. A writer’s first contact with their book was a private affair then, witnessed by a close circle of family and friends. It’s since become in the age of the iPhone an obligatory filmed performance of expectancy, joy, and awe, ideally with tears, ready to upload instantly across social media. There’s only one problem: I’m a terrible performer, unable to mask the mixed emotions I feel in most situations, unboxing one of my books very much included.

Books are sacrifices. They take years; they lock you alone in rooms; they pull you away from loved ones. When I met my now-wife, Jane, I’d just started my research for Moses and the Doctor. By the second date, I sensed that our relationship would blossom. Over the next seven months, right up to when I proposed to her, I didn’t write a word.

When I finally bore down on the proposal, I warned Jane that as soon as I signed a book contract, my free time would evaporate. Even on dates, some part of my mind would be mulling over how to get from point A to point B. Jane was nothing but encouraging, but I remained racked with anxiety, worried that a bout of writer’s block might plunge me into a self-destructive tailspin.

My first book, Our Team, was fraught. I turned in the first draft a year late and more than 80,000 words over the contracted count. For six months I revised furiously: eliminating chapters, jamming together sections, tearing down and then rebuilding the first half. By the time the manuscript went into production, I was convinced that it was an unreadable mess. When my finished copies arrived, I didn’t take a single photo. In my hands it felt like a funerary object for my brief writing career. It took me longer than it should have to accept that, chaotic revisions notwithstanding, the book was far from a failure.

I swore that I’d do things differently with Moses and the Doctor. I now knew how to research, how to write a chapter, how to figure out what to keep in and what to scrap. The challenge this time was my souped-up personal life. Seven months after I sold the proposal, Jane and I got married. Nine months later, we bought a townhouse. The following month, my wife went into labor. At the hospital, while she dozed, I huddled over my laptop and pecked away at chapter eleven.

Even after my daughter was born, I never felt that Moses and the Doctor was out of my control. Some days, I’d wake up at five a.m. to feed her and then started typing the moment she fell back to sleep. In the end, I turned in the manuscript on time and at the contracted word count. I had everything that I could’ve hoped for: a second book, a house, my two loves. So why wouldn’t the first glimpse of that spectacular cover of Moses and the Doctor elicit anything but unalloyed joy?

The short answer is: I’d garnered too much baggage in the years since I hatched the idea that mushroomed into this thirty-dollar hardcover to feel any emotion in its unalloyed form. All that time spent in libraries, in archives, in books, in my head grew heavy by the end, especially after notes on the fifth rewrite landed in my inbox. It’s not that I had mixed feelings about Moses and the Doctor—at least not in the way I did about Our Team near the end. But after reviewing the copyedits and the page proofs, I did need some distance from the book. Besides, it’s hard for me to fathom how anyone could endure the full publishing cycle and not question whether they’d want to do that again.

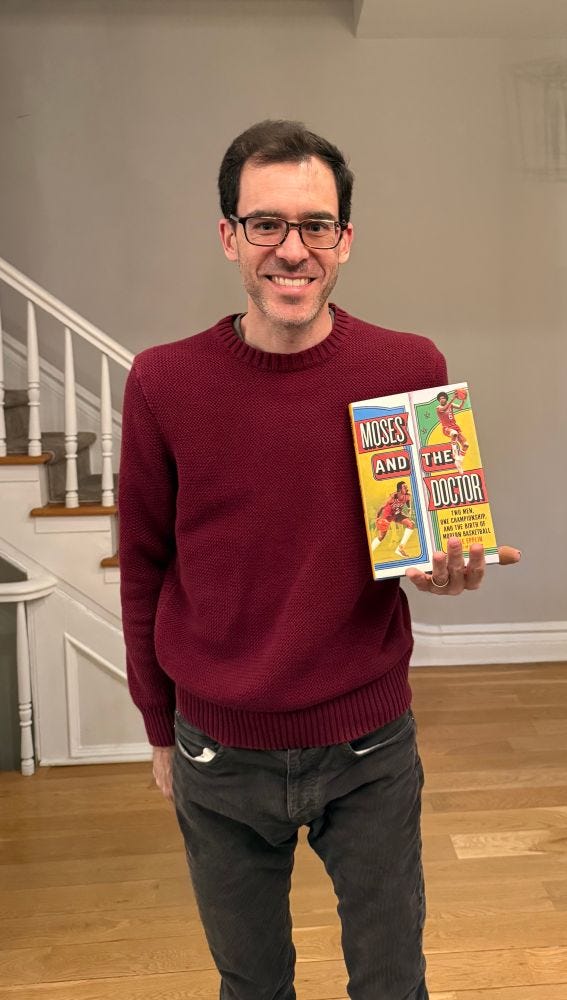

Luckily, the production process is long and I’ve spent the last four months without reading a single paragraph from Moses and the Doctor. When the box of books finally arrived, after Jane had returned from San Francisco, I asked her to snap some photos of me holding the first copy. (We tried to take a picture of my daughter holding the book, but she too is a reluctant performer.) Then I sent out the requisite posts on social media.

When my duties were all done, I cracked open the book and glanced over a few paragraphs at random. I no longer felt a knot in my stomach while reading them. I was at peace with what I’d done. It wasn’t joy necessarily and it certainly wasn’t suited to a thirty-second clip, but it was nonetheless the best, most gratifying feeling I could’ve hoped for in that moment.