When Bill Veeck purchased the St. Louis Browns in July 1951, the team already had settled into its customary spot in the American League cellar. True to his reputation as baseball’s foremost maverick, Veeck declared that the Browns’ season was as good as over. “I couldn’t very well go around insulting the intelligence of my audience by praising [the team],” he wrote in his autobiography Veeck—As in Wreck, “so I edged in through the back door by talking about the Browns as if they were the worst team that ever existed.”

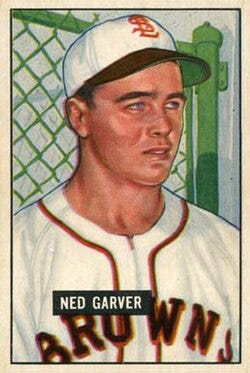

The lone player who didn’t fit that description was Ned Garver, the Browns’ pitching ace. Midway through the 1951 season, the twenty-five-year-old right-hander had accounted for half of the teams’ 22 wins. Improbably for a pitcher toiling on a team thirty games below .500, Garver was named the American League starter in that year’s All-Star Game. Never one to let a publicity opportunity slip by, Veeck mandated that the Browns “push Garver as hard as possible to help him become the first pitcher to win 20 games with a last-place team.” Garver would rise to the occasion, becoming the first—and, to this date, only—American League pitcher to notch 20 victories for a team that lost 100 games. It was a fitting feat for a player who was often at his best when his team was at its worst.

Garver’s fourteen-year tenure in the major leagues didn’t slot smoothly into many of the sport’s preconceived narratives. He was neither a hero nor a goat, neither attained World Series stardom nor suffered heart-wrenching defeat. Garver instead labored on a series of perennially mediocre clubs that faded from postseason contention shortly after Opening Day. Only twice—1955 and 1956 for the Detroit Tigers—did he pitch on winning teams; both seasons, the Tigers fell out of the pennant race before September. Garver was what I call a despite player—someone who excelled despite being stranded on losing clubs throughout his career.

A postseason-free career doesn’t necessarily imply failure. One of baseball’s legends, Ernie Banks, was the sport’s consummate despite player. The best-hitting shortstop of his era, he won back-to-back MVP awards in 1958 and 1959 for Chicago Cubs’ squads that finished 16 games below .500, cumulatively. So integral was Banks to keeping the Cubs respectable that Jimmy Dykes, a baseball lifer as a player and then manager, once quipped: “Without Ernie Banks, the Cubs would finish in Albuquerque.” During his nineteen-year tenure, Banks set what has become one of professional baseball’s most unbreakable records: he played in 2,528 games without ever competing in the postseason.

During the era when Banks and Garver played, it wasn’t uncommon for Hall of Fame–caliber players—from Luke Appling to Jim Bunning to Ron Santo—to endure career-spanning postseason droughts. The odds were stacked against them in several ways. Before 1969, October baseball was restricted solely to a World Series matchup between the top team from the American and the National Leagues. What’s more, the longstanding reserve clause bound players to their original franchise, prohibiting them from signing freely with more competitive clubs. Now, in a league where 12 of 30 teams advance to the playoffs each season and where athletes have greater control of their destiny through free agency, it’s increasingly unlikely that a star player would spend more than decade in the majors without ever sneaking into the Wild Card Series.

Since 1990, only one player, lumbering slugger Adam Dunn, has played in more than 2,000 consecutive major-league games without appearing in the postseason. In 2014, his last year in the league, Dunn’s Oakland Athletics’ club was eliminated by the Kansas City Royals in a do-or-die Wild Card game. Dunn, fittingly, sat on the bench for all nine innings. The longest current postseason dry spell is 342 games, held by Tyler Kinley, a relief pitcher who’s labored mostly on playoff-allergic clubs in Miami and Denver. A dwindling breed, “despite players” are going the way of the bullpen car.

Since sports are winner-take-all affairs, it’s natural to mythologize players on superior clubs as championship-caliber athletes whose tangible and intangible contributions cultivate a culture of winning that elevates their rosters. In contrast, it takes perspective and qualifiers (“resilient,” “dogged,” “consummate professional”) to celebrate those on lackluster clubs. “Despite players” are the Willy Lomans of professional sports: underappreciated practitioners whose once-promising careers were stalled by bad breaks or franchise dysfunction. They stand as reminders that the lives of professional athletes are capricious, fleeting, and not entirely within their control.

To put it in terms that Ned Garver would’ve recognized: Some players are signed by the New York Yankees, others by the St. Louis Browns.

Occasionally, however, players toiling on substandard teams produce seasons of unusual brilliance. Take Garver’s majestic 1951 season. His quest for twenty wins was messy, uproarious, exhausting, and weird; it also overlapped with two of the most notorious stunts in baseball history.

Since their improbable run to the World Series in 1944, the St. Louis Browns, struggling to stay solvent in a city that no longer could support two clubs, had sold off many of their top players for cash and spare parts by 1951. “We just didn’t have a traditional team,” Garver told me during a phone interview in November 2014. “We’d sometimes have an outfielder play first or a right fielder play third. The thing about the Browns is that they were also scrimping. You had to carry your own bags there. They were always scrimping on the doggone meal money. They were always trying to reduce it.” Equally challenging was the fan and media indifference. “Our ballgames never meant too much back then unless we were playing teams in pennant races,” Garver said. “Otherwise, the Browns would come to town and the writers would take the day off.”

Much of that changed when Bill Veeck took over midway through the summer. The second of Garver’s 1951 season was a co-production with the Browns new owner. No promotional stunt was too outrageous for Veeck. Here’s how The Sporting News described Garver’s third start after Veeck purchased the team, on July 20 against the Yankees: “One had to be in the park only a few minutes to appreciate the Bill Veeck touch—usherettes in snappy beach shorts, pyrotechnics, circus and vaudeville acts, and a breathtaking performance by a young lady who slid down a wire from one of the light towers across the field, dangling by her teeth.” As an afterthought, the paper mentioned that Garver went on to scatter six hits over nine innings, losing 1–0.

Veeck’s stunts intensified the following month. On August 19, Garver lost the first game of an afternoon doubleheader, then retreated to the clubhouse to shower. While getting dressed, he heard Browns’ radio announcers Dizzy Dean and Buddy Blattner express disbelief about the individual coming to bat. “I couldn’t figure out what was going on,” Garver recalled. “By the time I ran up to the dugout it was too late.” Eddie Gaedel, the three-foot, seven-inch little person whom Veeck had signed that morning, had already walked. Five days later, Garver took the mound for Grandstand Manager Night, a scheme cooked up by Veeck that enabled certain fans to vote on managerial strategy with Yes or No placards. Surrendering three runs in a complete-game victory, Garver took the stunt in stride—“I didn’t think much of it. I was just focused on pitching,” he said later.

In mid-September, with Garver stuck at 16 wins in the season’s remaining two weeks, Veeck instructed Browns manager Zachary Taylor to start Garver every third contest, giving him an outside shot at 20 victories. Garver won his next three starts but then ran into trouble during the season’s final game. With the score knotted at four apiece, Garver slugged the go-ahead homerun in the fourth inning—an appropriate ending for a player who had singlehandedly carried the Browns all year. Garver finished with a 20–12 record on a team that lost a whopping 102 games. The only other Browns’ pitcher to win more than five games that year was Duane Pillette, who finished with an undistinguished 6-14 record. Garver’s 20 wins were more than the combined total of the next four winningest pitchers on the Browns’ roster.

The gap between Garver’s personal triumph and the Browns’ collective failure cost him the Most Valuable Player award. The night before the announcement, an Associated Press reporter tipped off Garver that the award would go to him. But it wasn’t to be. Garver, Yankees catcher Yogi Berra, and Yankees hurler Allie Reynolds received six first-place votes apiece, but Garver fared less well further down the ballot. Berra took home the trophy during a season in which his Yankees won nearly twice as many games as the Browns en route to a World Series championship.

It hardly mattered that had Garver pitched for the Yankees—a team to which his name was perpetually linked in trade rumors—he might have made a run at 30 victories. Instead, he wound up in a familiar place: looking up, yet again, at baseball’s first division.

I first heard about Garver from my grandpa, a stalwart Browns’ loyalist. The stories he told me piqued my interest in a franchise that had departed St. Louis decades before I was born. When I was given a chance to write a book, my instinct was to make it about the Browns. Starting in 2014, I began calling the few Browns players who were still among us: Frank Saucier, Don Larsen, J. W. Porter, and, of course, Ned Garver.

Garver was forthcoming but humble, too self-effacing to crow about his accomplishments. The most revealing exchange came at the end of our hour-long conversation, when he said, apropos of nothing, “If I had to do it over again, I’d be more controversial, like Billy Martin. I was pretty blah. I just told the truth and told reporters that if I didn’t say anything interesting, then they shouldn’t write about me. I should’ve been more colorful, more entertaining.”

There was no time for follow-up questions. Garver was due at the hospital for dialysis. This much I knew: Garver didn’t want to be Billy Martin. He was too kind for that. He wanted to have had the same luck that landed Martin, a player not nearly as talented as Garver, on a New York Yankees squad that won five World Series titles during his seven seasons with the franchise. Garver wanted to have played on championship clubs where even colorless players saying colorless things commanded media attention.

His statement struck me as the ultimate despite player’s lament, a wish to be remembered, to be woven into the overarching narrative of his era. I hung up feeling somewhat sad. How could Garver not see that his 1951 season—the exceptional pitching, the perseverance, the stoicism amid demoralizing defeats and outrageous stunts—was every bit as memorable and colorful as anything else that summer?

Garver was a right hand pitcher, not a "Southpaw". The story was great however,

This is wonderful, Garver deserves the attention.